Origin myth by Nina Mingya Powles

My Poem of the Month for August is Origin myths by Nina Mingya Powles from her recent full-length collection Magnolia, 木蘭 published by Nine Arches Press. The poem, like so much of Powles’ writing, explores themes of belonging, family and identity.

The poem opens with a series of questions about a person’s origins. These questions include things like “where are you from?”, “where were you born?”, “how long has your family been here?” and “is this your home?” These questions set out to discover where someone is from, both in terms of where they were born and where their family come from. The questions could also be seen as a way of exploring a person’s claim to a particular place. Powles is a poet from New Zealand of mixed Malaysian-Chinese heritage and her poems are often about her mixed identity. In the poem, it feels as though the questions are being posed to some of a similar background to Powles and suggests that maybe she doesn’t have a claim on the place she is calling home. Questions such as “where was your passport issued?” and “what is your mother tongue?” implies that the person to whom the questions are being addressed may not belong to the city or country which they are currently occupying. Reading the first half of the poem makes me think about my own experience with belonging; the many times I have been asked where I am “really from”, the inadequacy of giving “London” as an answer to this question because the questioner cannot understand how someone who is not white can be from London. It reminds me of the time in school when a teacher was confused when I told her my nan is English, the same confusion my mother received when she was at school and people thought she was adopted because they couldn’t understand how a black girl could have a white mother.

Before the poem begins, Powles has noted that it was written in response to Lisa Reihana’s video installation Transit of Venus [infected] at the Royal Academy of Art, London. Reihana’s work was part of the Oceania exhibition at the RA in 2018, where entrance to the exhibition was free to New Zealand and Pacific Island passport holders. With this knowledge, these opening questions read like a questionnaire that a visitor to the exhibition may have had to fill out, especially with regard to the questions “where was your passport issued?”, “what is the purpose of your visit today?” and “what does this country mean to you?” The purpose of these questions could in fact be a way to reflect on a sense of belonging and attachment to New Zealand. Powles would have had free access to the exhibition and this poem might have been a way for her to write about the relationship she has with that country.

What I love about this poem is that it is not exclusionary. It does not reference a particular place and therefore anyone who reads it can think about the poem in terms of what it means to them. Issues of fitting in, or feeling part of a community, or calling somewhere home are things anyone can relate to. Whoever reads the poem will answer the questions in their own way, which is unique to them, just as no one’s lived experience is quite the same as someone else’s.

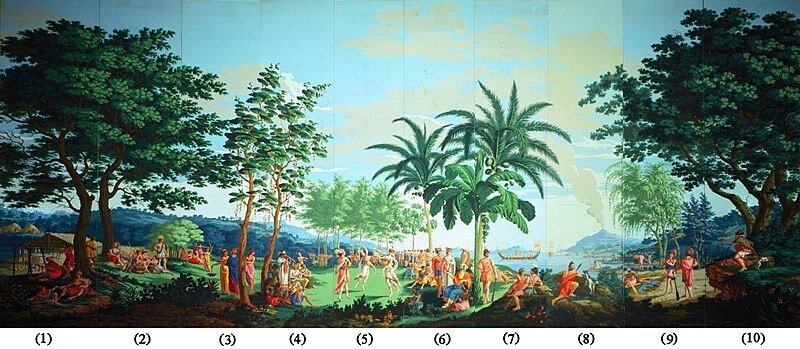

'Sauvages de la Mer Pacifique', panels 1-10 of woodblock printed wallpaper designed by Jean-Gabriel Charvet and manufactured by Joseph Dufour

'Sauvages de la Mer Pacifique', panels 11-20 of woodblock printed wallpaper designed by Jean-Gabriel Charvet and manufactured by Joseph Dufour

The second part of the poem is a series of statements which seem to be descriptions of the video installation, possibly written from the perspective of the artist. Reihana’s artwork is a panoramic video reinterpreting the French wallpaper Les Sauvages de la Mer Pacifique from the 1800s. The wallpaper was a twenty-panel scenic view, illustrating the widespread fascination with Captain Cook’s Pacific voyages with de Bougainville and de la Perouse. The exotic imagery of the wallpaper referenced popular illustrations of the time. Reihana reimagined the wallpaper, using Indigenous actors along with a complex and multi-layered soundscape. The poem describes the leafy landscape of the artwork, highlighting the “blue-green leaves” and the “small volcanoes [that] erupt slowly in the distance”. The poem makes reference to Captain Cook’s voyage with “a ship with white sails” and “they say the sun never sets on the British Empire”, and also to the fact that the original wallpaper from the 1800s was a completely fictional representation of the Pacific landscape and its peoples (“the imaginary trees cry out”).

One of the things I like most about the second half of this poem is the close attention to detail that helps to conjure such beautiful imagery. Lines such as “a woman’s voice is the wind”, “singing, dancing, an endless loop of sea…” and “a woman with feathers in her hair stands on the shore” create wonderfully vivid images, just as if you were looking at the artwork. I like the simplicity of the descriptions, which do not over-complicate and therefore do not take away from the message that is being conveyed. I also love how, toward the end of the poem, Powles switches the focus from observing to the act of making. She makes the artwork for us with the last four lines.

The structure of the poem is mirroring. There are fourteen questions followed by fourteen statements. It is possible to read the latter half of the poem as a response to the questions from the first. Although the second half do not straightforwardly answer the questions from the first half, there is a subtle relationship between them. For instance, the question “where was your mother born?” is answered with “they say the sun never sets on the British Empire”. This relation to place perhaps hints the person’s mother was born in a country ruled by the British Empire. Similarly, “is this your home?” is answered with “I stitch my name into the sea”. Calling somewhere home is to have a feeling of somewhere that is yours, to have some ownership over it. To stitch your name into something is also to have some ownership over it, just as when children have their names stitched into their school uniforms. These parallels give the reader just enough, but leaves it open to interpretation. Perhaps the person answering the question feels as though the sea is their home, or that the sea represents a vital part of where they call home.